HOW DID WE GET WHERE WE ARE?

In an attempt to end the war on drugs, states move to treat addicts rather than to jail them — scrambling to shift funds away from incarceration and toward treatment. PLUS: Update on Oregon’s move to decriminalize all drugs.

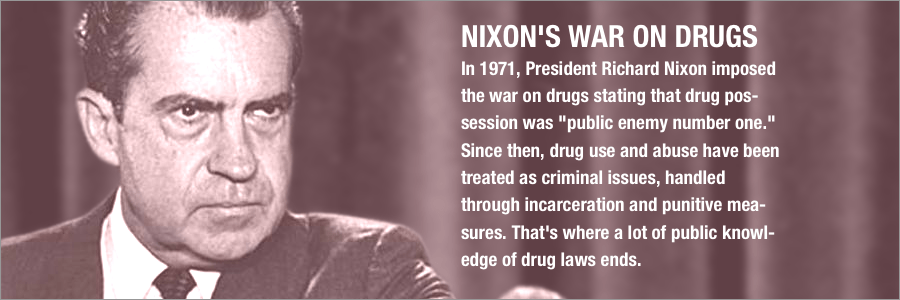

Since the first salvo in the War on Drugs — Richard Nixon’s attempt to incarcerate America’s way out of the a deepening drug crisis — it was all about punishing users, sellers -— everyone associated. It was an expensive policy, both in terms of tax dollars and lives ruined by the tough legislation — the result of which put a generation of Americans behind bars. Many of the addiction challenges that the United States would face throughout the following decades began in the jungles of Southeast Asia, as the Vietnam war hopelessly dragged on.

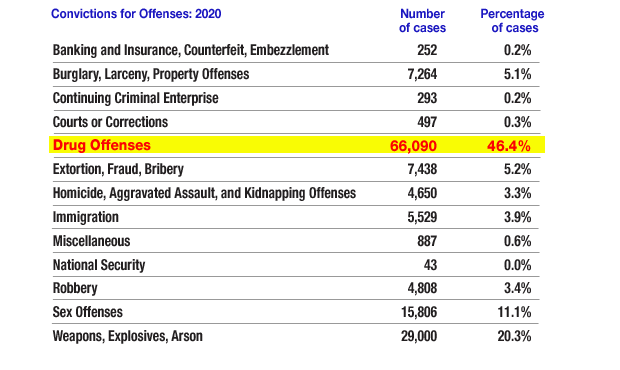

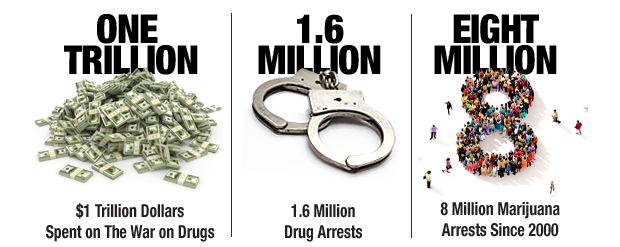

The War on Drugs by the numbers

- Amount spent annually in the U.S. on the war on drugs: $47+ billion

- Number of arrests in 2018 in the U.S. for drug law violations: 1,654,282

- Number of drug arrests that were for possession only: 1,429,299

- Number of people arrested for a marijuana law violation, 2018: 663,367

- Number of those charged with marijuana law violations who were arrested for possession only: 608, 775

- Percentage of people arrested in 2017 for drug law violations who are Black: 27% (despite making up just 13.4% of the U.S. population)

- Number of people in the U.S. incarceration in 2016: 2.3 million – the highest incarceration rate in the world

In 1971, as the war was heading into its sixteenth year, congressman Robert Steele from Connecticut and Morgan Murphy from Illinois, while visiting the troops, learned that over 15 percent of U.S. soldiers stationed there were heroin addicts. Follow up research revealed that 35 percent of service members in Vietnam had tried heroin and as many as 20 percent were addicted – the problem was even worse than they had initially though — and growing quickly both abroad and at home.

Nixon reacted, dramatically increasing the size and presence of federal drug control agencies, pushing through measures such as mandatory sentencing and no-knock warrants. Years later — even today — while many policymakers consider the War on Drugs a failure, others have nonetheless passed harsher sentencing laws and increased enforcement actions, especially for low-level drug offenses. The consequences of these actions are magnified for communities of color, which are disproportionately targeted for enforcement and face discriminatory practices across the entire justice system. To be sure, much of the stigma and underlying attitudes remain. The question in the minds of many has always been: ‘is drug addiction a disease or is it an avoidable affliction, fueled by the weakness of the individual?’ Punish the dealer, not the user.

Today, we recognize that drug addiction is a disease that has exploded into a public health crisis. Yet we continue our struggle to remove the stigmas associated with addiction, to provide more funding for those who seek care and cannot afford it, and to expand care into areas where COVID-19 and drug abuse have converged into a frightening tandem of death.

Is it time to sweep away the old rules and beliefs — to choose rehabilitation over incarceration? Can we at long last end the War on Drugs? While many see full decriminalization of all drugs — combined with public-funded treatment as the answer, others have reservations and concerns. Regardless, in liberal and conservative states — the people made their voices heard. They said loudly and clearly that “it’s time to end the drug war.”

While our ‘good angels’ work for treatment and rehabilitation for the addicted population (and right now we need it more than ever), the dealers, overseas suppliers, cartel bosses and gang members that unleashed and profited from their legacy of death must be brought to justice. The War on Drugs has made many of them very wealthy; they’ve got pockets-full of blood money and walk free while users needing treatment languish in prison.

The War on Drugs: Struggling for an effective policy

In 1972, a Nixon-appointed commission led by Pennsylvania Governor Raymond Shafer unanimously recommended decriminalizing the possession and distribution of marijuana for personal use. Nixon ignored the report and rejected its recommendations and thus began the long, winding path to current day. Between 1973 and 1977, however, eleventh states decriminalized marijuana possession. In January 1977, the Senate Judiciary Committee voted the decriminalize possession of up to an ounce of marijuana for personal use.

Within just a few years, the mood began to shift. Proposals to decriminalize marijuana were abandoned as parents became increasingly concerned about high rates of teen marijuana use. Then came Ronald Reagan…

Reagan goes on the offensive

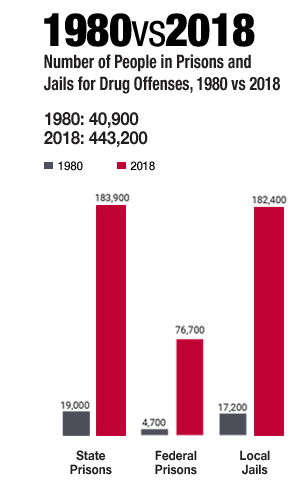

The presidency of Ronald Reagan marked the start of a long period of skyrocketing rates of incarceration, largely thanks to his unprecedented expansion of the drug war. The number of people behind bars for nonviolent drug law offenses increased from 50,000 in 1980 to over 400,000 by 1997.

Clinton talked the talk, but didn’t walk the walk

Although Bill Clinton advocated for treatment instead of incarceration during his 1992 presidential campaign, after his first few months in the White House he reverted to the drug war strategies of his predecessors by continuing to escalate the drug war and his controversial retention of the “three strikes” policy. Clinton also rejected a U.S. Sentencing Commission recommendation to eliminate the disparity between crack and powder cocaine sentences.

He also rejected, with the encouragement of drug czar General Barry McCaffrey, Health Secretary Donna Shalala’s advice to end the federal ban on funding for syringe access programs. Interestingly, a month before leaving office,Clinton told Rolling Stone magazine that “we really need a re-examination of our entire policy on imprisonment of people who use drugs,” and said that marijuana use “should be decriminalized.”

At the height of the drug war hysteria in the 1990s, a movement formed seeking a new approach to drug policy. The Drug Policy Foundation described itself as the “loyal opposition to the war on drugs.” Prominent conservatives such as writer William F. Buckley and economist Milton Friedman has long advocated for ending drug prohibition, along with civil libertarians and the ACLU.

Nevertheless the assault on American citizens and others continued — and still does to this day — with 700,000 people still arrested for marihuana offenses each year and almost 500,000 people still behind bars for nothing more than a drug law violation. This despite public opinion that has dramatically changed in favor of sensible reforms that expand health-based approaches, while reducing the role criminalization in drug policy.

Bush escalates; Obama fails to find the funding

George W. Bush arrived in the White House as the drug war was running out of steam – in response, he allocated more money than ever to it. His drug czar, John Walters, zealously focused on marijuana and launched a major campaign to promote student drug testing. While rates of illicit drug use remained constant, overdose fatalities rose rapidly.

The era of George W. Bush also witnessed the rapid militarization of domestic drug law enforcement. By the end of Bush’s term, there were about 40,000 paramilitary-style SWAT raids on Americans every year – mostly for non-violent drug law offenses, often misdemeanors. While federal reform mostly puttered during the Bush team, state-level reforms finally began to slow the growth of the drug war — with limited resources, they’d begin taking steps to address the problem locally in hopes of succeeding where the feds had failed with national policy.

President Obama, despite supporting several successful policy changes – such as reducing the crack/powder sentencing disparity, ending the band on federal funding for syringe access programs, and ending federal interference with state medical marijuana laws — was not able to shift the majority of drug policy funding to a health-based approach.

Upon its arrival, the Trump administration took action quickly. In March 2017, President Trump established the President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis, with the following stated mission: “to study the scope and effectiveness to the Federal response to drug addiction and the opioid crisis and to make recommendations to the President for improving that response.” The entire administration was mobilized to address drug addiction and opioid abuse by directing the declaration of a Nationwide Public Health Emergency to address the opioid crisis. As the epidemic expanded, the CDC launched the Prescription Awareness Campaign, poured $254 million into high-risk communities, law enforcement, and first responder coordination. The Justice Department brought Purdue Pharma and others to trial and convicted them. And yet, the damage has already been done — hundreds of lives are still being lost each day to addiction. The COVID-19 pandemic has crushed the recovery of many and has led to a heartbreaking rise in overdose deaths. The war on drugs, it seemed, would rage on. Another noble, but ultimately ineffective attempt to ‘right the ship’ after fifty years of failed policy. People are dying and our prisons are filling. Are we still punishing — rather than treating — addiction?

The Biden administration has now taken over. Clearly, Biden is intimate with the addiction epidemic. The president’s own son, Hunter Biden, has had a long struggle with addiction including alcohol and drugs. The ACLU has publicly declared that “President Biden should issue an executive order within his first 100 days declaring an end to the war on drugs and directing his federal prosecutors and law enforcement to use their discretion to stop prosecuting the war on drugs. Thousands of people are prosecuted in federal court for drug possession and prosecutors have failed to adequately use their discretion to decline these cases, let alone to not seek incarceration as sentence. This must end. An executive order by President Biden should also incentivize states to end the war on drugs, where the large majority of incarceration for drugs takes place.”

Only time will tell if the war on drugs will continue or it we’ll finally put an end to the criminalization and begin the process of healing.

Fast forward: Oregon leads in decriminalization efforts

Oregon became the first state in the United States to decriminalize the possession of all drugs on Nov. 3, 2020, with Washington state right behind.

Measure 110, a ballot initiative funded by the Drug Policy Alliance, a non-profit advocacy group backed in part by Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, passed with more than 58% of the vote. Possessing heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine and other drugs for personal use is no longer a criminal offense in Oregon.

Oregon’s move is radical for the United States, but several European countries have decriminalized drugs to some extent. There are three main arguments for this major drug policy reform in Oregon…

They Believe drug prohibition has failed Decades of research has found the deterrent effect of strict criminal punishment to be small, if it exists at all. This is especially true among young people, who are the majority of drug users.

They Believe decriminalization puts money to better use The Harvard economist Jeffrey Miron estimates that all government drug prohibition-related expenditures were $47.8 billion nationally in 2016. Oregon spent about $375 million on drug prohibition in that year.

They Believe the drug war targets people of color Another aim of decriminalization is to mitigate the significant racial and ethnic disparities associated with drug enforcement.

This is Oregon’s reaction to its overwhelming addiction crisis. Their theory: problem drug abuse is a public health challenge to be manage, not a war that can be won.

Reversing that failed policy

Katherine Beckett, Chair of Law, Societies, and Justice Department at Oregon State University told an NPR audience that Oregon voters’ decision to decriminalize drugs could become the model for Washington state and others. “I think that it’s really exciting that Oregon voters have expressed this recognition that the war on drugs is a failed policy and it absolutely is a failed policy in so many ways,” Beckett said.

Washington’s ‘rehabilitate don’t incarcerate’ strategy

Meanwhile in Washington state, marijuana has been legal since 2012, but possession of hard drugs such as LSD, methamphetamine, and heroin has remained a criminal offense. However, Washington is following Oregon’s lead and presenting a legislative bill entitled ‘The Treatment and Recovery Act’ to decriminalize hard drugs in 2021.

Christina Blocker, press secretary for Treatment First Washington, the campaign organizing the legislative bill, explained the goals of the Treatment and Recovery Act. “We’d be first reclassifying personal use drug offenses from crimes to civil infractions and the connecting individuals with the right services to address the underlying causes of their substance use disorder, really to just help them get back on track,” Blocker said.

Addiction is UNDENIABLY a public health issue (a crisis, actually) and other countries are proving it can be treated like one.

There are risks with any major policy change. The question is whether the new policy results in a net benefit. But there are reports of successful public health policy: In Portugal, full decriminalization has proven more humane and effective than criminalization; users don’t worry about facing those criminal charges. Those needing help are more likely to seek it – and get it.

Portugal’s overdose death rate is five times lower than the EU average which is itself far lower than the United States’. HIV infection rates among injection drug users have also dropped massively since 2001. Perhaps a lesson to be learn — that punishment isn’t the answer?

We should look forward to a future where drug policies are shaped by science and compassion rather than political hysteria. The war is over.

Let’s punish the criminals, save the victims, banish the stigma, and put the failed War on Drugs in our collective rear-view mirror.

Appendix: The scale of The War on Drugs

It’s measured in dollars and lives. What is now seen as a failed policy has affected the perception of addiction and treatment to this day. Can officials create a sea change and move to ‘treatment first?’

Harsh sentencing laws such as mandatory minimums keep many people convicted on drug offenses in prison for longer periods of time: in 1986, people released after serving time for a federal drug offense had spent an average of 22 months in person. By 2004, people convicted on federal drug offenses were expected to serve almost three times that length: 62 months in prison.

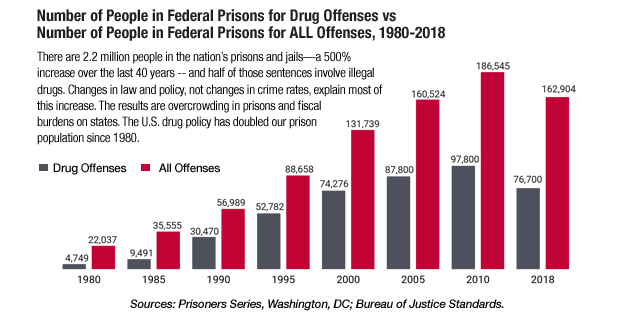

At the federal level, people incarcerated on a drug conviction make up nearly half the prison population. At the state level, the number of people in prison for drug offenses has increased nine fold since 1980m although declining in recent years. Most are not high-level actors in the drug trade, and most have no prior criminal record for a violent offense.

Sentencing laws like mandatory minimums, combined with cutbacks in parole release, keep people in prison for longer periods of time.

The National Research Council reported that half of the 222% growth in the state prison population between 1980 and 2010 was due to an increase of time served in prison for all offenses. There has also been a historic rise in the use of life sentences: one in nine people in prison is now serving a life sentence, nearly a third without the possibility of parole.

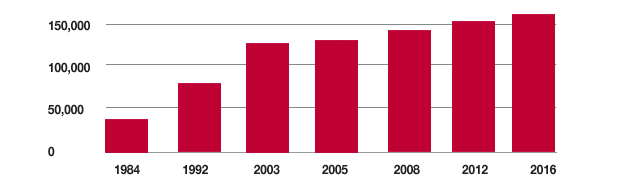

DRUG OFFENSE INCARCERATION

Minor drug convictions are dominating our legal and corrections systems, clogging our courts and overpopulating our prisons.

Along with the drug lords and gang members that end up in the prison system, there is a large population of non-violent inmates, convicted and sentenced under the strict guidelines of the 1990s, guilty of mere possession of illegal drugs. Shouldn’t the legal system focus on the criminals who’ve profited from the War on Drugs, while offering to help the victims?